|

There are a few momentous dates in history when we can remember

where we were or what we were doing, the assassination of J.F. Kennedy,

the death of the Princess of Wales or the events of 9/11. For the

Hindu fishing community of Alappard on the south-west coast of India

the 26th December 2004 was a normal day. The men were at sea in

their fishing vessels. It being a Sunday the children were off school

and their mothers or grandparents were looking after them. For those

in the community who had televisions, they were switched on with

India’s breakfast television broadcasting the usual mix of

entertainment. Then the normal programmes were broken into as news

flashes began to report an unfolding disaster on the other side

of the country. The news was confused. It seemed that some kind

of natural disaster had come from the sea and a picture of devastated

communities along the east coast of India began to emerge. At that

stage no one had heard of, let alone knew what a Tsunami was.

The people of Alappard gathered around their televisions and initially

watched and listened to the news about the unfolding events hundreds

of miles away. Eventually, after about an hour people began to drift

back to their normal chores and duties. A few minutes later shouts

and cries were heard coming from the beach and at the same time

a loud noise started to come from the sea. The people panicked.

They ran home for safety. For those who did make it home, their

doors and windows were smashed open as a deluge of water burst in

and quickly filled the rooms. It had been about 2 hours since the

Tsunami had hit the east coast of India. For some 15 minutes people

found themselves scrambling for their lives inside their own homes.

The water receded. People began to escape from the “safety”

of their homes. The panic remained, not only amongst the residents

but also among the police who arrived to help. Still no one knew

what exactly had happened. It was night fall before the population

were evacuated inland and it was only at that stage that people

began to realise that friends and relations were missing. The fishermen

from the community arrived home oblivious to what had happened.

It was 24 hours after the disaster before the people and relief

agencies were able to return to Alappard to commence a search.

India's Paradise Coast

Some 130 people, mostly women and children (the men were at sea)

were lost from Alappard. Miraculously, the bodies of all were recovered.

As we know, this is a story that was repeated in communities all

around the Indian Ocean following the Boxing Day 2004 earthquake

and resulting Tsunami. Many fishing communities were affected. The

aftermath witnessed a tremendous outpouring of sympathy and aid

from around the world, not least from the people of Northern Ireland.

Their affinity with the affected fishing communities led local fishermen

to start their own fund and during the first half of 2005 over £20,000-

was raised by the industry and friends of the industry in Kilkeel,

Annalong, Ardglass and Portavogie.

There has been much debate in the 2 ½ years since the catastrophe

as to how the vast amount of money raised globally was used. From

the outset the organisers of the Northern Ireland Fishing Industry

Tsunami Appeal gave a commitment that they would report as to how

the funds they had raised would be spent. And it was to help achieve

this that I travelled to Southern India in mid-May to see some of

the Tsunami affected areas there, meet the fishing industry and

visit Killai, the fishing community in Tamil Nadu, south-east India,

which was adopted by the local appeal.

Some of the facts about India are staggering. The population of

the country is over 1.1 Billion (nearly half as big again as the

entire continent of Africa) who are squeezed into a country of 11

million square km (less than a third of the size of Africa). Over

80% of the country’s population are Hindu and about 2% are

Christian. But amongst the fishing communities of south-west Indian

state of Kerala, some 48% of fishermen are Christian. This can be

partially attributed to the colonisation of India by Europeans,

which started in the early 1500s when for obvious reasons the adventurers

arriving from Europe on sailing trips, bringing with them Christianity,

confined their explorations to the coastal areas. India also has

a Christian tradition stretching back many centuries before the

Europeans arrived.

A night time approach into the airport at Trivandrum, Kerala’s

state capital was initially confusing. The in-flight map was showing

the aircraft over the sea, but looking out of the window the view

was composed of hundreds of lights against a pitch black background

as far as the eye could sea. Driving into the city from the airport

one of my first questions to Nalini Nayak, my host in India, was

to seek an answer to what I had seen from the aircraft. Nalini confirmed

that the in-flight map was correct – I had been over the sea

and seen some of the hundreds of small fishing vessels “light

fishing”. I would see these “vessels” up-close

the next morning.

Nalini herself is an enigma. Coming from a land-locked region of

India, she chose to follow a “career” with the fishing

industry before leaving university. Initially attracted to Kerala

to find out more about the world’s first democratically elected

Communist government, Nalini quickly discovered the injustices faced

by the region’s fishermen, even within the Communist system.

Nearly forty years later Nalini, with her colleague A.J. Vijayan,

continues her work with fishermen throughout India and other parts

of the world, as well as devoting much of her time to other important

causes, most notably women’s rights.

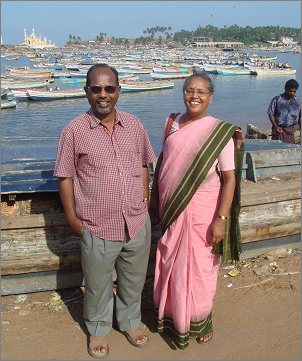

My hosts in India: A.J. Vijayan and Nalini

Trivandrum is near India’s southern tip and the area is fast

becoming a tourist destination. But away from the tourist compounds

and misleading headlines about India’s development, the staple

industry along the coast remains fishing, with traditional fishing

communities and villages strung out all along the coastline. One

such village is Vallakadavu, adjacent to Trivandrum’s airport.

A variety of vessels are launched from the beach. Increasing fuel

costs are encouraging a revival in traditional fishing vessels,

amongst the most popular of which is a craft built of four logs

tied together, on which 3-4 men will fish with hooks and lines.

Larger, motorised vessels allow fishermen to travel further out

to sea, while beach seine netting is popular all along the coast

and employs up to 40 men per team. Men and women are actively involved

in the fishing industry throughout India. Traditionally men catch

the fish, while the women buy and sell it.

Men and women working together

in the fishing industry

During my visit there were so many occasions when in conversation

with fishermen and fisherwomen I closed my eyes and imagined I was

back at home. The problems were just the same, with reduced catches

and marketing issues at the top of the agenda. The catching sector

is largely un-regulated. Seasonal spawning closures corresponding

with the monsoon season are welcomed by many fishermen, but apparently

abused by many others. The enforcement of any regulations that do

exist is practically non-existent. All the fishermen that I spoke

to were of the opinion that fisheries management was needed, but

the management process had to emanate from the industry. The over-arching

issue for the Indian Government is that fishing provides much needed

food and employment in a country of 1.1 billion plus people.

During the trip several days were spent travelling to and getting

acquainted with the fishing communities. Visits to different fishing

villages and harbours, fishing associations, ship yards and India’s

main fisheries laboratory were included in a hectic schedule. As

well as me finding out about the issues facing India’s fishermen,

fisherwomen and wider industry, everyone was keen to find out about

the fishing industry back in Europe. Indeed, they were aware of

many of our problems, which as I have mentioned mirrored their own.

A new 20 metre steel fishing vessel, built in

three months. Cost £37,000

A conscious decision had been made when organising the trip that

everything would be done the Indian way. For example, Indian hotels

were used in preference to western owned hotels and in temperatures

of 40’C+, cold showers became a welcome relief, which was

fortunate as hot water was not available most of the time. Practically

every form of transport was used, from motor scooters to the highly

efficient Indian railways. When it came to eating everyone was very

aware of the risks associated with India’s delicious, but

very spicy cuisine and while the fear of the dreaded “Delhi

Belly” was real, not once was a problem encountered, mainly

thanks to the dietary consideration of my hosts for their visitor.

One valuable lesson arose when with three of my new Indian friends

we visited a popular restaurant in Trivandrum where I bought dinner.

The shock came when the bill arrived and I had to pay the grand

total of £4- (including tips) for the entire feast, a cost

that typified all charges in the real India!

Throughout Indian society there is great deal of emphasis placed

upon education. During my stay in Trivandrum the results of the

state exams (the equivalent of our GCSEs) were announced. Sadly,

as well as reporting the success of the students, the headlines

in the local newspapers for the next few days announced the death

of several children, mainly girls, who having failed their exams

had committed suicide.

In some respects there was quite a bit of disquiet about the education

system that allegedly favoured the better-off in society. Children

from fishing families are generally speaking less well off and as

a result there was a tendency for them not to perform so well in

their exams. Better news came in the shape of the Sr. Rose Memorial

Education Resource Centre, which had been established to provide

after-school coaching to children from local fishing families. In

many ways the work of the institute is inspirational, not least

because it is largely funded through the efforts of Robert P who

comes from a fishing background himself. Boys and girls attend the

institute for 4-5 hours each day after school and are encouraged

to do so by their parents. The result of this extra tuition is impressive.

Two years ago the pass rate in the local main stream schools averaged

35%. In the same year 100% of students who had attended the institute

passed their exams, a feat that was repeated last year. The result

is that many children from the fishing families have been able to

progress to higher education, with one former student now practicing

medicine in England. It was nice to learn that many former students

express their appreciation for the Institute by making regular donations

to its running costs, although outside financial help continues

to be needed.

The 'fishing' children at the

Education Resource Centre

Twenty-first century politics, and what some might claim to be

progress in Indian society is having a tremendous impact upon the

fishing industry and this was brought home to me when I reached

Chennai, India’s fourth largest city, found on the east coast

of the country. Even in the city there is a large vibrant fishing

community, which for obvious reasons is based along the coast. Chennai

was on the front line when the Tsunami hit on the 26th December

2004 and with the fishing communities based along the shore, it

was these people who bore the brunt of the disaster.

In advance of the Tsunami the State Government in Tamil Nadu had

been trying to move the fishing community, not out of safety concerns,

but rather because they wanted to clear the slums in which the fishermen

were living to make way for re-development in the shape of new luxury

hotels and apartments. The fishermen resisted and on one day the

resistance cost the lives of eight fishermen who were shot by local

police.

Shortly after the tsunami hit, the states’ First Minister

was helicoptered into one of the affected communities to view the

devastation. She wasn’t there too long when an alert came

through that a second wave was approaching. As she made her way

back to the helicopter, the local fishermen allege that she and

some of her officials were laughing, because as she seen it, nature

succeeded in doing the work that the Government had failed to do.

Chennai, where a fishing vessel is shown

washed ashore by the Tsunami

The fishing communities in Chennai were devastated. The politics

of the situation discouraged charities from offering assistance

to these people. The State Government did offer to build replacement

homes, but on the condition that they would be 15 miles away from

the coast – something that for fishermen was going to be just

a little hard to cope with. So, after refusing the Government’s

help, the fishing communities were abandoned. Had it not been for

the assistance offered by their union and a few local activists

it seems they would have lost hope. Two years after the disaster

the union managed to raise sufficient funds to enable them to build

a few permanent homes. In Tamil Nadu the classification of a permanent

home is a building with four concrete walls, measuring 20 feet by

10 feet, with a tiled roof. As the new homes have been built to

the Government’s specification, they cannot be forcibly demolished.

These homes have no electrical or water supply, or sanitation. They

consist of one room and are often home to large family groups. However,

despite the conditions and lack of official support their owners

do have a pride in their homes, both inside and out.

As I walked through these areas people were extremely welcoming

to the “light skinned person”. The smiling children

were very keen to have their photographs taken and as soon as the

digital camera was produced groups of kids gathered around asking

for their pictures to be taken and then wanting to look at them

on the small screen, something that caused much amusement. At one

stage a mother came running with her nine year old daughter by the

arm and I automatically assumed she was wanting me to take a photo

of the girl. But she wasn’t. Instead, through the interpreter,

the mother asked if I would take her daughter home with me, to a

place where she thought her child would have a better life. This

was one of the very difficult circumstances I found myself in. How

do you reply in a situation like that?

A new permanent home for

fishing families in Chennai

A seven hour drive south brought us to the community of Killai,

the village that our local Fishing Industry Tsunami Appeal had agreed

to sponsor. Prior to the Tsunami Killai was a community of three

villages. The “mother” village was located a little

way inland along an estuary, while the other two villages were located

on the coast. When the Tsunami struck the community, the two outlying

villages were washed away with a substantial loss of life. The “mother”

village survived, mainly due to its location and the fact that the

natural mangrove forests that surrounded the village had not been

removed and so absorbed much of the wave’s energy. Around

the two coastal villages, like many other similar villages around

the Indian Ocean, the mangroves had been removed to make way for

development, including shrimp farms. The removal of this natural

breakwater allowed the Tsunami to hit these communities with its

full force. People from the mother village came to the assistance

of their friends and relations in the other two villages and there

are many stories of bravery to be told, bravery that saved many

lives.

Killai can be described as being true rural India. In many of these

villages people had never seen “light skinned” people

until the relief effort kicked in after the disaster. There is still

a degree of suspicion towards foreigners, not least because when

the “relief effort” arrived the locals consider that

they were not consulted by many aid workers as to what exactly was

needed, but rather were told what form any relief offered would

take. The population is very aware of the vast sums of money that

was raised in the UK, Ireland and throughout the world and they

are extremely grateful for it. They are also aware that for a whole

variety of reasons a lot of this money has never reached its intended

beneficiaries. Yet, as they point out a great deal of money did

get through and has made a positive difference.

Many of the families lost everything. I noted that some of the

women were wearing gold jewellery, while others were not. There

is no banking system in these parts of India, so if people save

any money they tend to buy gold, which they wear on very special

occasions. On a normal day the gold is left at home. ‘Boxing

Day’ 2004 was such a normal day, so when the wave devastated

the coastal villages many people’s life savings, their gold,

was washed away.

Killai is a fishing community and the fishermen there still favour

traditional fishing methods. Unlike many neighbouring communities

they prefer man-powered canoes over motor boats. As with fishing

communities in the other parts of India I visited, the men are in

charge of catching the fish, while the women are in charge of selling

the catch. Community decisions are still very much dominated by

the men and in the meeting I had with the community’s representatives

in the village hall, the women had to wait their turn before having

what was in effect a separate meeting.

Killai Village Centre

Something else that some might regard as being very similar to

home was that the women knew exactly what help they wanted. The

men did not. The women had their plans formulated and articulated

them well. Even during our meeting the men were still discussing

what exactly was needed.

The women were and are keen to pursue a long-term sustainable development

project. They had identified land in the village that they could

purchase. On that land they planned to build a centre, which would

incorporate a small factory that would employ up to 75 local women.

This factory would produce paper and paper products that they could

then sell to make more money to plough back into further community

development work. The women proposed that they be allowed to spend

some of our funds to buy the land. If this was approved the local

Government had agreed to match-fund the money and build the centre.

The equipment had already been sourced for the equipment needed

to make the paper and some training had been provided. Copies of

land deeds and other supporting documentation were produced to reinforce

their presentation. Everything had been well planned and co-ordinated.

After some hesitation, the men said they wanted fishing nets. Unfortunately,

as the conversation progressed it became obvious that they didn’t

know how many nets, or of what type. They didn’t know what

the nets would cost. Nor could they tell Nalini and myself how long

they would last. I found myself in a strange situation, trying to

explain to the Killai fishermen what Government officials back in

the UK would say to me if I asked them for a 100% grant to buy fishing

nets. I know it was a different situation, but with Nalini I told

the fishermen that if they wanted our help in purchasing nets, which

we were not ruling out, then they would have to present this as

part of a management plan designed to create an economically viable

and sustainable fishery. They protested that this could not be done

without the involvement of surrounding fishing communities (all

of this should sound very familiar to local fishermen). Our response

to that was to get on with it, something that was easy to say, but

greatly assisted by the involvement of the local union representative

who volunteered to co-ordinate the activity. The men have been given

until October to come up with this plan.

So in short, none of the funds raised by the Northern Ireland Fishing

Industry Tsunami Appeal has actually been spent and indeed most

of the money (£18,000-) remains in an account here. Some £6,000-

is in an account in India. No doubt this will come as a surprise

to many and indeed initially it proved to be very frustrating to

me, until I thought about it. Throughout my visit to India I heard

how funds meant for Tsunami relief had gone missing or had been

mis-spent. In Killai, while the community were very thankful for

much of the aid they had received, they were critical of the way

much of the money had been allocated, without their input.

Meeting with Killai Village Representatives

So far as our fund is concerned, which so many local people contributed

to, we know where all the money is and hopefully how it is going

to be spent. It will not be used on short-term fixes. It will not

be used on administration. It will not duplicate the efforts that

have already been made by others. Rather, by showing a lot of patience

and working directly with the affected people it will be used for

what the people in Killai want and that should result in the creation

of a legacy that will generate a long-term and sustainable income

for the people of this part of India. Who knows, maybe offices like

ours will be able to buy and use some of the paper products made

by the women in Killai? After our meeting in Killai with the village

representatives, Nalini and I were invited back to one of the homes

for Sunday lunch. There was a reason why this home had been chosen.

It was one of the very few houses in the village with four concrete

walls. Why was this family so lucky? The answer was because the

‘man of the house’ had spent several years away from

home working on a building site in Singapore. In fact, one week

after my visit he was returning to Singapore on another twelve month

contract. I suggested to him that this must be very hard on himself,

as well as his wife and young family. He agreed, but pointed out

that because of this sacrifice his family could enjoy a much better

standard of living and hopefully his children could look forward

to a better future. We enjoyed a sumptuous Sunday dinner sitting

on the floor of his home, having various fish dishes served to us

on a leaf from a banana plant. The “light skinned person”

was made to feel very much one of the family.

India is a fascinating country. There are many extremes. The mix

of poverty with many happy, smiling faces summed the situation up.

People knew that they were stuck in a situation where it is extremely

difficult to find a better standard of living. Life for tens of

millions is a daily struggle, but there is hope, that is typified

by the Institute in and the attitude of the women in Killai. It

is through the help of people like us that the Indian people can

have a better future. There final words to me were to please thank

everyone in Northern Ireland and especially our fishing communities

for everything they already done. Just be patient.

I am not the first person from Kilkeel to witness the “sights

and sounds” of India. I hope I can return to Killai in the

not too distant future to see the progress the people have made

there with your and my money. In the meantime I would like to say

a big thank you to all those who contributed to the Fishing Industry

Tsunami Fund, which allowed me the chance to have and share this

experience.

« Back to News |